Introduction

/The 50s was a decade of mostly stagnancy, where society tried to hold on to the status quo after the upset of WWII. The 60s then was an explosion of new ideas, fighting against the conformity of the previous decade. Before the 80s came around with a new form of capitalist conformity by putting everything in neat, commercial boxes, the 70s happened.

The 70s in in movies was a time of extreme experimentation, building on the new ideas of the 60s and figuring out what was possible. And beyond what was possible. Movies became more even more progressive, more daring, more sexual, more violent. It was ‘most significant formal transformation since the conversion to sound film and [was] the defining period separating the storytelling modes of the studio era and contemporary Hollywood.’ (Berliner 2010).

But it had other consequences as well. Women for the first time in movie history played a significant, noticeable role (ignoring all the controversy around ‘Jeanne Dielman’ topping the Sight & Sound list, it’s the prime example of a female filmmaker using the opportunities of the 70s for a long lasting impact). It was also the first time that horror became really marketable and not just for a while, but for good. Black cinema saw an ‘explosion in the production of black-themed, black-cast motion pictures’ (Sieving 2011) and found commercial success through Blaxploitation. Even pornography became part of the mainstream for a while. Non-American movements found resonance internationally, especially with films from Germany, Australia but also still France, Italy and Spain. Queerness came out of its shadows and was more or less embraced (but also its stereotypes, as Vito Russo makes very clear). And on top of all of that, apart from all the more indie progress, it was also the decade where the blockbuster was created, which in one way or another lead to the end of this era. Pauline Kael describes the beginning of the decade as if ‘three decades seem to have been compressed into three years’ (Kael 1973) and that feeling can be extended to all of the 1970s, in society but also in culture, including movies.

This introduction will give an overview of some of the central aspects of the decade. Most of these will get a more in-depth look further down the road.

Caligula, a big Budget movie with real starts but also extreme violence and Hardcore sex

Deep Throat and The Devil in Miss Jones, two of the most commercially successful hardcore porn films of the decade

Jaws, the beginning of the blockbuster

The 70s at the Oscars

As an entry point to see how this decade is different from any other (which of course is true for any decade), let us take a quick look at the Best Picture winners at the Oscars during the 1970s:

1970 Patton: A film that in subject and scope is close to many epic war films of the 1960s but already includes elements (like the opening segment) that have a 60s (and then 70s) sentiment. It is not really rebellious or provocative but more morally ambiguous than previous films in this genre.

1971 The French Connection: A gritty police thriller with morally dubious protagonists and a documentary-like style that also includes a ground-breaking car chase. What doesn’t really sound like a Best Picture candidate, became a blueprint for the future. No Best Picture winner had ever looked like this.

1972 The Godfather: New Hollywood made its splash over to the box office and the Academy Awards. Coppola became most successful trendsetter for the new generation of directors that planned to overtake Hollywood.

1973 The Sting: While this film features some indie elements, it also felt like a short break of a film looking back at Old Hollywood. Gangsters, the 30s, lightweight managed to beat its more art house nominees.

1974 The Godfather Part II: Sweeping the Oscars with a sequel was unusual enough, doing with a different way of structuring a story helped to set another trend for the future.

1975 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest: The adaptation of a 60s provocative critique of society had Jack Nicholson with a once-in-a-lifetime performance. And at this point it almost seemed normal that a film with such a pointed view at institutions could win the main awards.

1976 Rocky: While the film developed into a crowd-pleasing franchise for decade, the original film was an underdog story full of unknowns without a triumphant ending.

1977 Annie Hall: Another breach into the awards business - the intellectual comedy, almost purposefully trying to distance itself from the mainstream while still appealing to its notions of romance.

1978 The Deer Hunter: The final hurrah for New Hollywood at the Oscars, as Michael Cimino manages to confront the nation with its recent trauma in an epic, unrestricted way.

1979 Kramer vs Kramer: While dealing with issues that hadn’t been featured prominently in Hollywood films, the story of a divorcing couple and single father packed enough sentimentality to safely guide audiences into the 80s.

Few decades (if any) featured so many films as Best Picture that both were revolutionary for the film industry and would become instant canonized films. If anything, this speaks for the unique power of this decade. It was as if movies were growing up.

The 70s at the Box Office

During the first half of the 1970s, New Hollywood manage to strike some surprising hits. Among the many successful films were the documentary about the Woodstock Festival (1970, directed by Michael Wadleigh, $50 million), The Last Picture Show (1971, Peter Bogdanovich, $29.1 million), A Clockwork Orange (1972, Stanley Kubrick, $114 million), Billy Jack (1971, Tom Laughlin, $32 million) and its sequels.

This continued in one way or another throughout the decade, but there was also another side to this equation. Star-studded disaster films like The Poseidon Adventure (1972, Ronald Neame, $125 million) or The Towering Inferno (1974, John Guillermin, $203 million) also ruled the box office in that first half and then came the blockbuster with Jaws (1975, Steven Spielberg, $123 million at the time, over $400 million until today) and then ‘Star Wars’ (do you really need the numbers for this one?) and then it was all about topping the box office and stars and effects.

Still, the box office in the 70s was as diverse as it would ever be. Deep Throat and The Devil in Miss Jones became hits, despite being X-rated hardcore porn movies. Bruce Lee and the Shaw Brothers put Hong Kong cinema into theaters all over the world. The Exorcist was the first horror movie to become the most profitable film of a year. In India, Sholay saw the release of probably the most successful Indian movie of all time in 1975.

Still, by 1979, the box office was already dominated by superheroes (Superman), sequels (Rocky II), TV show adaptations (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, The Muppets Movie), franchise sequels (Moonraker) and sex-driven comedies (10), which doesn’t make it seem like a time far far away.

The Horror, The Actual Horror

Horror movies weren’t really relevant anymore, after their last resurgence in the 50s and even despite the breakout success of Rosemary’s Baby and The Night of the Living Dead at the end of the 60s. But that changed monumentally with The Exorcist (1973, William Friedkin). Again, it made more many than any horror film before. It managed to get an incredible 10 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture (winning two), which wouldn’t happen again until the 90s. It also caused enormous controversy, among religious groups, because of the effect on audiences, because of the conditions under which it was made. It was an absolute sensation, changing how the genre was perceived forever, making it ‘the most important of all American genres and perhaps the most progressive.’ (Wood 2003)

It opened the door for other horror films. Despite some people strangely suggesting it’s not a horror film, Jaws (1975, Steven Spielberg) became another horror movie with even more success (among other things, leading to short wave of animal horror films). The previous year, Tobe Hooper made one of the most notorious and influential horror films of all time with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. After Black Christmas (1974, Bob Clark) as a precursor, John Carpenter popularized the slasher with Halloween (1979) for the following decades. The Omen (1976, Richard Donner) became a blueprint for evil child movies. Carrie (1976, Brian de Palma) was the first of endless Stephen King adaptations. George A. Romero continued his zombie legacy with the wildly popular Dawn of the Dead (1978). 1979 saw the first of many Alien (Ridley Scott) films of sci-fi horror. Another box office smash hit, The Amityville Horror (1979, Stuart Rosenberg) established the haunted house trope again for a new generation. And in Italy, Dario Argento and Mario Bava made waves with a new sub-genre, the giallo, like Suspiria (1977), while their contemporary, Lucio Fulci, after dabbling in giallo as well, reached new heights (or lows, considering the quality) of gory zombie films with the ridiculously titled Zombi 2 (1979).

Yes, the 30s had the Universal monsters,the 60s had Hammer Films, the 80s had all the famous slashers and the 90s had Scream and its influences, but no other decade was as groundbreaking and influential as the 70s when it came to horrify audiences. One reason might be that ‘there was a lot more to be afraid of in the seventies’ (Muir 2002), considering the political climate and the aftermath of the Vietnam War (which influenced the revolution of make-up effects by people like Tom Savini, who used his war experiences directly for creating realistic wounds). Another reason might be that the rule breaking mood of the decade was especially important for horror films, as they were willing to go to any extreme and were finally able to not just hint but simply show anything gruesomely imaginable.

The Decade of the Scandal Movie

Movies have always created scandals, from the razor blade meeting an eye in Un Chien Andalou (1929, Luis Bunuel & Salvador Dali) to anything Lars von Trier has made. But the 1970s seemed to be especially concerned with stirring audiences and testing their limits. The aforementioned The Exorcist might be the most popular example but also relatively harmless compared to other films. Again, this was mainly due to the fact that anything seemed possible, anything could be filmed and shown on screens and enough filmmakers saw opportunities what to do with that rare freedom. Audiences had always been interested in sex and violence, now was the time to show both as explicit as possible.

Last Tango in Paris (1975) is still debated over its depiction of sex between Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider, or to be more precise, over the way these scenes were filmed by Bernardo Bertolucci. Never before had a big name actor like Brando (fresh off his success with The Godfathers) been willing to re-enact sex acts that some audience members probably had never heard before. Nagisa Oshima went even further with In the Realm of Sense (Ai no korida, 1976) where the two main performers actually had unsimulated sex, which was shown on screen in every detail. Outside of porn films, this had never been dared before, even less so when the film combines sex with violence.

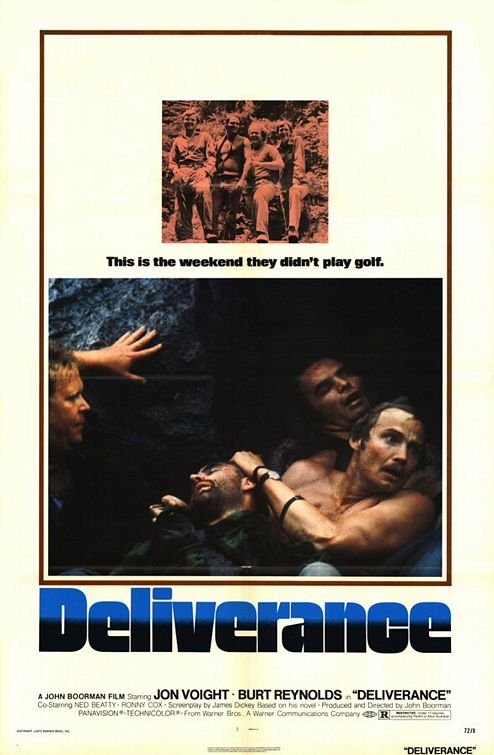

Horror films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Last House on the Left (1972, Wes Craven) were simply too much for many viewers. While the former was rather bloodless (and still extremely scary), the latter had no qualms in showing the ‘cruel violence employed by [a] gang as they prey on the innocent and the feral savagery of crazed parents hungry for their pound of flesh’ (Crane 2002). Similarly, Deliverance (1972, John Boorman) shocked people with violence but also with a male-to-male rape scene that became infamously iconic.

The combination of sex and violence also lead to discussions about the purpose and effect of films like The Devils (1971, Ken Russell), A Clockwork Orange or Straw Dogs (1971, Sam Peckinpah). Same for one of the most controversial rape-revenge films I Spit on Your Grave (1978), Meir Zarchi, later pseudo-feminist re-titled as The Day of the Woman) which made Roger Ebert in his 0-star review wonder if the audience members’ positive reactions made them ‘vicarious sex criminals’ (Ebert 1980).

The scandal movie to end all scandal movies was certainly Salò (1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini), which depicted the sexual and physical torture of a group of young people by an fascistoid elite fo almost two hours and made people question its artistic value until today. The scandal movie attempting to end all scandal movies, by hiring its own protesters, was Snuff (1975, Michael Findlay et al), where almost no one doubted that it absolutely no artistic value.

Porn Chic: The Golden Age

Certainly the most unique and singular developments during the 70s was the breach of hardcore porn movies into the mainstream. Movies with explicit sex scenes and close-ups making box office money, being watched by average moviegoers, discussed in newspapers and on television, reviewed by actual film critics. How was that possible? And why did it stop?

The reason for it happening is more or less simple: just like in every genre during those years, there seemed to be no limits for what could be shown on screen anymore. In horror, that meant mostly guts and gore, but nothing is more interesting to audiences than sex. And nothing had been more taboo ever since the 30s and the Hays Code. Inspired by movies from Sweden, first attempts at showing explicit sex were met with outrage but also interest. Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie (1969) is seen as the starting point and Deep Throat (1972) as its sleazy breaking point. Deep Throat ‘was innovative not only for its close-ups of ejaculating penises (“money shots”) and shameless hard-core sexuality, but for its integration of pornography with feature-length narrative structure’ (DeAngelis 2007). It film broke so many barriers and was so incredibly successful that it inspired many imitators, including filmmakers who attempted to make arthouse porn movies, like Behind the Green Door (1972) or The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976).

You could argue that these attempts never really made the jump to the other side of ‘serious movies’ but for that short period in film history, there was the possibility that showing detailed sex could become the norm. But towards the end of the decade, the VCR was introduced and the possibility of making many cheap porn films with such an easy distribution meant the end of ‘porn chic’.

The New Auteurs

While the 70s end with the resurgence of studio power, the first half is still driven by ‘directors whose personal vision and artistic talents were less hampered by either a domineering studio system or moribund censorship standards’ (Friedman 2007). They represented ‘a new generation of film-school educated directors’ (Webb 2014) and now made some of their groundbreaking films that would guarantee them an entry in film history books forever (with some of them just in their thirties at the time). Some examples:

Martin Scorsese went through a whole career arc in just one decade, from early celebrated films like Mean Streets (1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) to the spectacular flop of New York, New York (1977) that seemed to punish him for his ambitions. He survived, of course, and most importantly his Taxi Driver (1976) became one of the most significant movies of all time.

Steven Spielberg had a similar trajectory. Duel (1971) and Sugarland Express (1974) earned him respect, Jaws (1975) made him eternally famous, 1941 (1979) is still seen as his biggest flop.

Francis Ford Coppola probably had the three biggest films of any director during the 70s. The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979) all were instant and long-lasting impactful films, regularly earning top 10 spots in movie all-time lists. The Vietnam film almost broke him personally, but it was One from the Heart (1981) that marked the end of his zenith. And compared to Scorsese and Spielberg, he never reached those heights again.

Robert Altman had a bigger output than some of his contemporaries, which made his hits seem smaller and his flops less destructive. MASH (1970), Brewster McCloud (1970), McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973), Nashville (1975) and 3 Women (1977) stand critically acclaimed next to mostly forgotten films like Images (1972), Thieves Like Us (1974), Quintet (1979) and A Perfect Couple (1979). But even Altman then entered a dry run that would last until the 90s.

Peter Bogdanovich has a clear split between three major hits (The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc, Paper Moon), followed by increasingly less successful films (from Daisy Miller to Saint Jack). Unlike some of the others, he is almost entirely remembered for these three 70s films because their impact was so strong.

One common aspect of course is also the fact that these are all men. Female directors were able to become more visible in the 70s, with Lina Wertmüller (getting two Oscar nominations), Liliana Calvani, Chantal Akerman, Barbara Kopple, Gillian Armstrong and Elaine May as the most prominent. That most of them were not treated with the same reverie as their male colleagues and that they had definitely less opportunities in future decades reminds us that it would still take a long time until history books recognized them and their influence was noticeable.

The Politics of Politics

It’s almost impossible to read a description of the 70s cinematic landscape without seeing it as a reflection of the political landscape. With events like the final years of the Vietnam War, the Watergate Scandal, the international oil crisis, the German Autumn, it seems logical to assume that this influenced the fiction of the time. But, of course, every decade is full of historically impactful events and they always, well, have a cultural impact. And while political themes can be found and analyzed in movies from any decade, the 70s stand out as having a high number of explicitly political films. This doesn’t necessarily reflect on the political climate as on the artistic climate, which allowed more diverse themes to be used for narrative fiction and directors getting away with more straightforward political messages (see also Berliner 2010).

Thus, it is interesting to notice these films and analyze them, pointing out its obvious themes and messages, seeing political discourse so clearly laid out on screen. We have films dealing with current developments, the paranoia thrillers inspired by Watergate (e.g. The Parallax View, All the President’s Men), the first wave of post-Vietnam films (e.g. Coming Home, The Deer Hunter) to more general dissections of government and authority (e.g. Punishment Park, Il conformista/The Conformist), media (e.g. Network, Die verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum/The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum), workers’ rights (e.g. Harlan County, USA), religion (e.g. The Devils, Carrie), capitalism (e.g. La classe operaia va in paradiso/The Working Class Goes to Heaven) and many, many more. There’s also a string of films for the first time really dealing with the Holocaust and the Nazi regime (e.g. Die Blechtrommel/The Tin Drum, Pasqualino Settebellezze/Seven Beauties).

While these films lean more towards left-wing attitudes, there was also more explicitly conservative approach to films, most prominently the vigilante films inspired by the success of Dirty Harry (1971) and Death Wish (1974). These films are the minority, for sure, but political films still ran both ways.

Black! Exploitation?

The other most significant development of this decade were new opportunities for black filmmakers and performers. Black cinema became more popular in general, as Hollywood made a little bit more room for black characters in mainstream movies (even if it was often one token black character). But this era is mostly remembered (somewhat unjustly) for the subgenre of Blaxploitation, a mixture of black cinema and exploitation, as the title implies.

Blaxploitation is mostly seen from two, often extreme, angles. Either it’s a phase that empowers black people by giving them black heroes on screen, often fighting against racism. Or it reinforces black stereotypes by focusing on criminals and celebrating misogyny. The truth, as is often the case, lies somewhere in-between. On top of that, blaxploitation films are often reduced to a money-making scheme by white producers to exploit the increased interest in black content. But ‘the removal of African American agency from accounts of the production and reception of 1970s black-themed cinema allows […] the claim that the institutional racism embedded in the American film industry has always mitigated against the expression of a true African American consciousness’ (Sieving 2011), thus reducing an important development to a mere interesting but not serious footnote.

The impact of the biggest films of this era can not be underestimated. Shaft (1971, Gordon Parks) wouldn’t have been remade/requeled twice (in 2000 and 2019) if it was just some cheap film. Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1971, Melvin van Peebles), often seen as the first real blaxploitation film, couldn’t be more experimental in its style and controversial in its themes (especially about sexuality). There’s a reason Pam Grier managed to have a career based on her many blaxploitation appearances, in particular the two Jack Hill features Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974). It’s easy to find many flaws in the black Godfather-version Black Caesar (1973,), the black-Dracula version Blacula (1972, ) or the seeming glorification of the pimp lifestyle in Super Fly (1972, Gordon Parks), but these were still important films that help to shape a new narrative and venue for black stories in cinema.

But instead of a purely black sub genre made specifically for black audiences, ‘the studios decided that black and white audiences wanted similar fare - action, sex and violence in urban-cop, drug, and caper movies’, so it ‘seemed easier and more safely profitable to replace the black film with the 'crossover' film (like Sounder (Twentieth Century-Fox, 1972) and Lady Sings the Blues (Paramount, 1972)) in which black themes and roles are filtered through white sensibilities so that the movies can be marketed to white as well as black audiences.’ (Izod 1988) This trend continued to great success in the 80s as seen by broadly marketed vehicles for Eddie Murphy or Whoopi Goldberg.

International Waves

The 60s had seen an eruption of film movements in different countries that often inspired American filmmakers (and in the long run all over the world) to change the way they made movies, most famously La Nouvelle Vague with François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, the most influential cinematic impact since German silent cinema. While both directors continued to make successful films in the 1970s, the French New Wave had mostly died down (again, except for the strides French female directors like Chantal Akerman and Agnès Varda made). A similar development happened to the Japanese New Wave, which still produced notable films like In the Realm of the Sense (1976, Nagisa Oshima), but essentially ended at the beginning of the 70s (Desser 1988).

The German New Wave also sparked in the 60s, but it was the 70s, fueled by the radical political unrest happening in Germany, where some of the most important post-WW2 German films were created. If nothing else, Rainer Werner Fassbinder all by himself was a cinematic force that seemed to be unstoppable, pushing forward the medium by incorporating American influences into his very unique style. But also his contemporaries like Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Volker Schlöndorff (winning the first Academy Award for Germany in 1979) and Margaretha von Trotta showed the potential of German cinema and ‘during 1977/1978, almost 60 German feature films were made, of which roughly half belonged to the New German Cinema,’ (Elsaesser 1989) a ratio that seems astounding.

The Australian New Wave in the 1970s started because the government-established Austrian Film Development Corporation (AFDC) helped finance movies in a way that hadn’t happened before. This wave is harder to categorize because the films are so diverse and while it is known for making directors like Peter Weir (The Cars That Ate Paris, 1974, Picnic at Hanging Rock, 1975), George Miller (Mad Max, 1979) and Gillian Armstrong (My Brilliant Career, 1979) famous, it initially began with so-called ‘ocker films’, comedies about masculinity in Australia, like Alvin Purple (Tim Burstall, 1973), which was a huge hit and ‘showed that Australians would watch films about themselves, especially those that exaggerated the comic elements of character’ (Aveyard, Moran & Vieth 2018).

Sources:

Aveyard, K., Moran, A., & Vieth, E. (2018). Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema. Rowman & Littlefield.

Berliner, Todd (2010). Hollywood Incoherent: Narration in Seventies Cinema. University of Texas Press.

Cook, David A. (2000). Lost Illusions-American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam 1970-1979. University of California Press.

Crane, Jonathan L. (2002). Come On-A My House: The Inescapable Legacy of Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left. In: Mendik, Xavier (ed.), Shocking Cinema of the Seventies. Noir Publishing.

DeAngelis, Michael (2007). Movies and Confession. In: Friedman, Lester D. (ed.), American Cinema of the 1970s. Rutgers University Press.

Desser, David (1988). Eros plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave. Indiana University Press.

Ebert, Roger (1980). Review of ‘I Spit on Your Grave’. Chicago Sun-Times.

Elsaesser, Thomas (1989). New German Cinema. Macmillan and Rutgers University Press.

Izod, John (1988). Hollywood and the Box-Office, 1895-1986. MacMillan Press.

Kael, Pauline (1973). Deeper Into Movies. Little Brown.

Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland & Company.

Russo, Vito (1995). The Celluloid Closet. Harper & Row.

Sieving, Christopher (2011). Soul searching: Black-themed cinema from the march on Washington to the rise of blaxploitation. Wesleyan University Press.

Webb, Lawrence (2014). The Cinema of Urban Crisis: Seventies Film and the Reinvention of the City. Amsterdam University Press.

Wood, Robin (2003). Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan—and beyond. Columbia University Press.