Blow Out (1981) [1981 Week]

/Blow Out (1981)

Starring John Travolta, Nancy Allen, John Lithgow, Dennis Franz

Director of Photography: Vilmos Zsigmond

Music by Pino Donaggio

Edited by Paul Hirsch

Written and directed by Brian de Palma

Rating: 9,5 out of 10

(spoilers ahead)

Blow Out is an incredibly cinematic movie but it never becomes just an exercise in moviemaking by actually having something to say. Still, director Brian de Palma uses every trick in the book to enhance this story and to (often) visually explore an aspect of moviemaking that is not visual: sound. That alone is fascinating to watch but the movie also works as a dark conspiracy thriller about a disillusioned generation that mourns the 60s and 70s. John Travolta delivers a great performance here with a wide range of hopelessness, excitement, anger and despair. But this is a director’s movie and I’m not the first to suggest that this might be de Palma’s finest moment both as a director and a writer. The use of split-screens, change of focus with special lenses, long takes and a circling camera (in one spectacular scene that doesn’t ever seem to stop) are impressive and effective at the same time. After watching so many movies from 1981, this one stands out so spectacularly that even weeks after seeing it, it makes me feel good to see so much passion on the screen.

One aspect that I love about de Palma in general but I especially enjoyed here, is the idea of commenting on the process of making a movie, of a meta-fictional attempt to make the viewers aware of what they are watching. De Palma uses several techniques for that. The first is the brilliant opening sequence that mimics a typical slasher movie. The idea to do that right when slasher movies were at a peak (in 1981 alone Halloween II, Friday the 13th Part 2 and My Bloody Valentine were released) is brilliant enough, but apart from doing it a unique way (with a lot of long takes and Steadicam, being more inventive than the movies it mocks) while still making fun of it, the viewers are then confronted with the fact that they are just watching a movie. Within a movie.

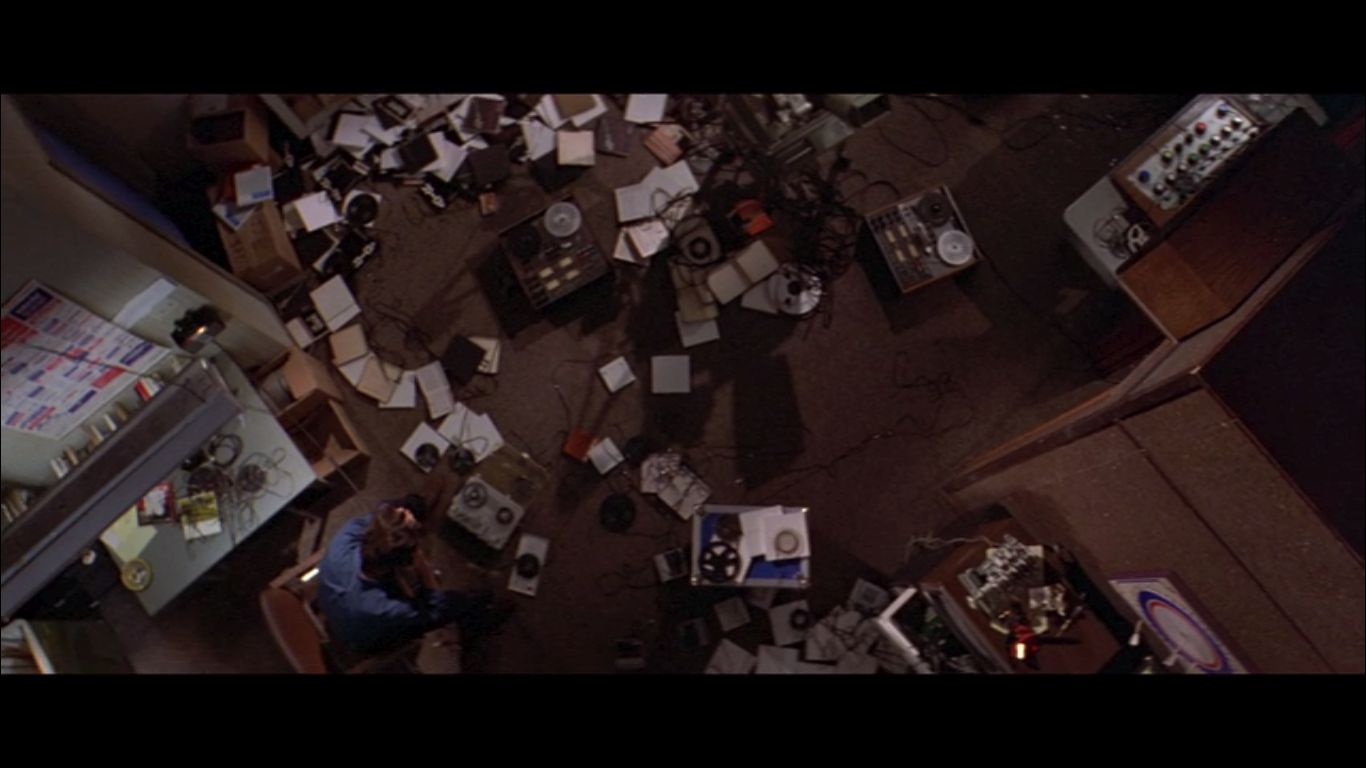

I have expressed my joy for meta-fiction before (because I think it serves as an effective device to teach people to question what they see) but something about it here is especially gratifying. Throughout the film, the idea of using sounds to distort the image we see in movies is brought up again and again and later in the film we watch Jack Terry (John Travolta) basically making a little movie all by himself, which is very fascinating to watch. The movie uses this process to raise the question of authenticity; by seeing how something is made and can be changed through sound and images, the viewer has to question the validity of such images in other contexts.

Ideologically the movie shows Jack as a character who had a lot of potential in his youth and tried to use it to do good. This attempt fails horribly, with the death of a policeman and he retreats to working in the sleazy B-movie business, fully aware of the waste of his potential there. After being a witness to the car accident and saving the Nancy Allen character he finds hope again and tries to redeem himself by bringing this conspiracy to light. But we’re in the 80s now and times have changed. Now it’s not his fault anymore but society which tries to bring him down at every stop, denying him any chance of uncovering the lies that are brooding underneath the surface of images and sounds that are used in the media.

Sally (Nancy Allen) has an interesting function, even if it makes her a bad representative for women in a movie full of men. She still has the American Dream in her head, which therefore makes her extremely naïve. As a representation of an illusory ideal that has driven many people into misery this works really well. In the end, not to subtly, this ideal is literally killed, expressing clearly that in 1981 there is no room for optimism and hope anymore. Sally, as the ideological representation of traditional American values, is abused and murdered and Jack, representing the ideological revolutionary who wants to change the situation, ends up more hopeless and desolate than in the beginning of the movie.

The last images of Jack just succumbing to his despair because he doesn’t see any possibility to do good anymore in this world, is haunting and excels the movie to yet another darker level. Jack in the end learns the credo of his time, which is not to have actual ideas that are fueled by passion, but to cling to detachment to somehow endure the indifference of society. What’s special here is that while in other 1981 movies the characters embrace detachment and sometimes seem to celebrate it, Jack fights again and again to avoid becoming as detached as everyone else, but fails in the end. He realizes it’s the only way society will let him survive. There are few movies having the guts to end in such a bleak way.

I have to thank the Projection Booth podcast for their excellent episode on Blow Out and for hinting at many ideas I have incorporated here. Credit where credit’s due.