Our Life Is a Movie: The Cabin in the Woods (2012)

/(spoilers ahead)

Cabin in the Woods is a very clever movie that seems innocent and surely will fly by many people. But it’s so many things at once. It’s a decent horror movie, a comedy, a great work of metafiction and, most importantly, an amazingly intriguing comment on our society. It’s extremely well made and acted, and all in all a really bold movie. Since it appears in this series, I obviously love it.

The movie’s main interest is to play with tropes and stereotypes. Its main story focuses on a typical horror movie plot in which teenagers enter a cabin in the woods and are murdered one at a time. It then turns this concept on its head, by revealing that this horror story is just a manufactured scenario to stop the world from ending. It’s a very complex movie that looks simple, which makes it all the more impressive. I’ll try to focus on specific aspects to not get lost in my own analysis.

The treatment of tropes is split into two areas: there are the horror movie victims tropes and the horror movie monsters tropes. The victims are introduced traditionally and later in the movie, explicitly named and even pictured with big stone symbols: the whore, the athlete, the scholar, the fool, the virgin. This is part of the metafictional appeal of the movie (and plays on similar grounds as the Scream movies), but it also functions as a comment on society. Watching horror movies, we accept those simple categories as if that was how people are. As I have pointed out before, stereotypes are prevalent in our culture because they simplify life for us, especially if we don’t realize how much harm they cause. Movie tropes reinforce that attitude because they show us again and again that people fall into specific categories and there is not much way to get out, thereby reducing our willingness to question stereotypes in real life. If you see a certain trope often enough, it becomes hard to see anything else in people.

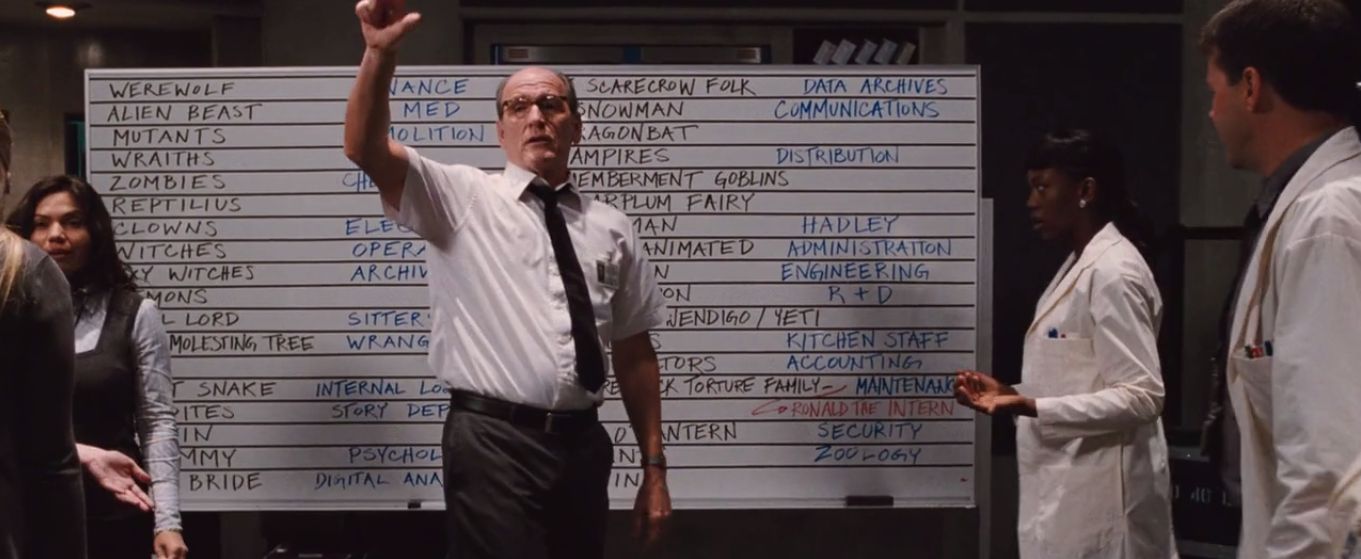

The stereotypical victims also fulfill a metafictional purpose because as the film reflects upon them, so does the audience, becoming are that those are tropes of movies and what their function is. This is even more true of the monsters in the film. The infamous flip chart of all the monster/villain stereotypes is fun enough, but showing them all off in the grand finale is not just great geek entertainment, it’s also the nod to the viewer to say: We’re in a movie and we remind you of all those movies. That the movie tries to find a logical explanation for that metafiction makes it even better, I think, because it is more than just showing off. It grants us a peek into our cultural mindset by claiming that there is a purpose behind all those tropes. But we’ll get to that in a second. So, even here the movie works on different levels: it’s exciting and scary because there are lots of monsters, it’s geeky because it lets you guess which monster is which and it’s intelligent because it makes you reflect upon the whole idea of monsters.

But let’s go to the ending and the crucial points of the movie. All through the movie we are told more and more about the mechanisms of why the victims are killed and the monsters are chosen, that it’s an old ritual to stop some evil from destroying the world. In the last scenes the Director (Sigourney Weaver) (the director! how metafictional can you get?) appears and explains everything to the last two survivors. Five young tropes have to be killed or otherwise

They rise. […] The ancient ones. The gods that used to rule the Earth.

I don’t want to get all Daniel Quinn here (again, I’m saving that for October/November), but this could be interpreted according to his ideas. Which, quickly, boils down to the idea that our (flawed) culture might be the main culture on our planet, but not the only culture. It’s also the youngest culture. Humans have been living on this planet for a long time and it worked well until our culture came along. I know, this simplifies things a lot, but this is not the time and place for more. The point is, the movie, or the Director, tells us that our culture is built on a system of sacrifices, a system that requires stereotypes to suffer so that our culture can live on before the ancient ones decide to come back. “The world will end,” she says forcefully. Marty, the fool, (Fran Kranz) replies with my favorite line of the movie that sold it to me completely:

Maybe that’s the way it should be. If you got to kill all my friends to survive, maybe it’s time for a change.

She tries to convince them by scaring them, telling them it’s not change, but everyone will die horribly. She boils it down to our culture’s favorite, the binary either/or decision: “You can die with them or you can die for them.” After a fight and killing the Director, the two are left contemplating the end of their world that they have brought upon them and everyone else. Dana (Kristen Connolly) goes

Humanity… It’s time to give someone else a chance.

There’s another joke and then the worlds ends through the giant hand of an ancient god. (don’t you wish more movies could be described by sentences like this?)

Besides the fact that this ending is so bold in being a happy and unhappy ending at the same time and not making the two survivors kiss in the end, it puts a heavy thinking piece on the audience (if they see it). Unfortunately in that last quoted line the movie goes for humanity again, which lessens the impact (because, again, if humanity is the problem, we have no hope; if it’s just our culture, there is hope). It’s time to give another culture a chance is probably asked too much, but would have been even better. But still, the movie depicts a culture that thrives on stereotypes and is ruled by a clinical, authoritative and emotionless system that assigns categories to people and makes them pawns in a game. In the end, the two remaining pawns decide to end the game because they think anything new can only be better than this. This is why “humanity” is not so problematic here, because it’s clear that it might be an end, but there will also be something else again. It’s not the end. And the sentiment that something new can only be better is so warming to my hopelessly idealistic revolutionary heart, to hear that in a Hollywood movie, to have that as the ending of a movie that plays so much with the rules we’re accustomed to and that we too often accept without questioning them, to be forced to question them, even just by geeking out and laughing about them; all of this makes this a great and, despite all its campy entertainment, an important movie.