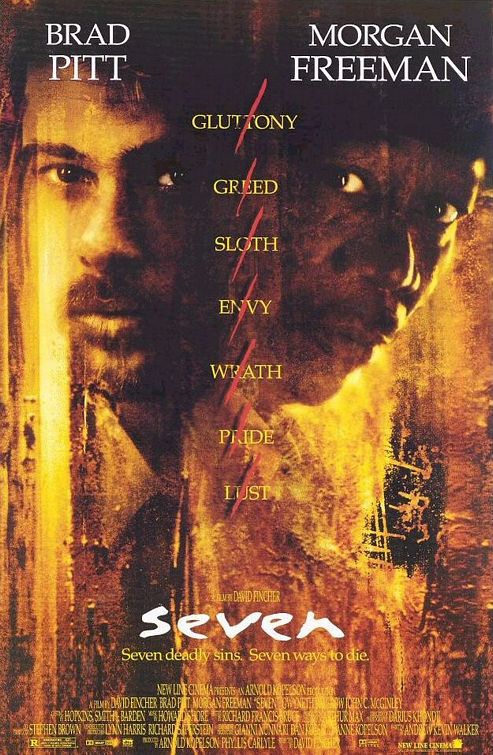

Our Life Is a Movie: Se7en (1995)

/(spoilers)

When I saw Se7en for the first time in a theatre in the fall of 1995, it was a revelation for me. The opening credits, the atmosphere, the structure, the acting, David Fincher’s brilliant direction and above all the twist ending took me by surprise and somehow showed me what movies can do. I watched it again in the theatre just a week later, because I had to experience it again as soon as possible. It was also responsible for me going regularly to the theatre after that, starting a long stretch of cinema visits that cemented my initial childhood love for movies far into adulthood. In that aspect, Se7en is of great importance to me personally, a huge influence for my movie-watching capabilities. I have seen it so many times over the years (I once watched each of its seven days on separate days) and when I watched it with a class for the first time this January, I loved it just as much and saw also clearly what it means for my world view and why I still consider it an important movie when talking about our culture. I won’t explain any plot details, I’ll just assume that you know the movie and if you don’t, go and watch it.

The main question of the movie is how to react to the terror of this world: do you try to change it and fight “evil” or do you become detached and passive to endure what you experience? Of course, the basic assumption for this question is that the world is evil and the movie does its best to prove that point. The movie is dark and bleak, probably as dark as a movie can be. There is almost no sunlight and instead there is the movie’s characteristic constant rain. Characters use flashlights all the time, they ran through sinister apartment buildings, sit in offices at night or go sex clubs that feel like you’d imagine hell. It’s the city that holds them like a concrete prison, with no room to breathe and relax, no silence ever (the sound design is brilliant and never lets you off the hook), only to be hurt or lonely.

The loneliness of the characters in this world is emphasized again and again. The opening shot of Somerset (Morgan Freeman, reminding you how good he actually can be) in his apartment, going through his morning rituals. His loneliness is visible right from the start and the way his colleagues dislike him enhance this impression. Although the credits start with Brad Pitt, it’s Freeman who is the protagonist of the movie, looking at this world with weary eyes. But Mills (Pitt, not going for the easy hero by being somewhat annoying), with all his optimism (more on that in a second) and his wife also seems lonely. And Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow, also very good in her few scenes), confesses later in the movie just how lonely she feels and how much the city wears her down. The sadness in her eyes speaks volumes what this world does to people.

Somerset and Mills do find a connection eventually and it becomes the heart of the movie. As detailed in Every Frame a Painting’s wonderful essay on David Fincher, the way Fincher shows their relationship improving through simple cinematic tricks is impressive and important for us to see, that there is some hope in this world. But this is not the story of two cops hating each other and becoming best friends. They disagree, right until the very end, about their task in this world. That they are able to be there for each other despite their differences gives us some hope, but the discussions they are having are the conflicts we are fighting in this world every day. Again, the basic notion is undeniable: this world (in my mind, this culture) is awful, reinforcing isolation, greed, ignorance and pretense.

The movie offers four ways of responding to this world, as represented by its four main characters. Tracy stands for despair, she simply can’t stand or deal with the ugliness of this world and is so overcome by sadness that the thought of her pregnancy scares her. John Doe (Kevin Spacey, simply unforgettable) goes the other direction. He hates this world and wants to change it by punishing people for committing sins, in other words, for making the world a terrible place. Mills thinks he just has to do good to overcome evil, to fight “the good fight” long enough and to never give up. Somerset finally is the most torn, wanting to retreat to apathy, but not yet really giving up. So, despair, hate, fight or retreat.

Now that’s an interesting model in itself, but Fincher and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker are smarter than giving us archetypes. Tracy is not just a weak, sad woman, she actually seems stronger than Mills and though she reaches out to Somerset for help, she is more aware of what is happening around her than her husband. On the surface, Tracy becomes the literal woman in the refrigerator in the final cruel twist of the movie. Her death is the impetus for the man’s character development. But I think the movie sidesteps that idea by first making her a round, multi-faceted character that you will remember as more than a head in a box and second her death doesn’t really develop Mills’ character. His reaction is wrong, it just triggers his impulsive aggressiveness that has got him into trouble all through the movie.

John Doe is also superficially making the wrong decision, but in his monologue in the car, he argues well enough to make it hard to completely disregard his idea. Sure, when he talks about god and his mission, you laugh him off, but he makes many points that seem at least conceivable. And he also accuses people of being apathetic, of not caring enough, which is also Somerset’s opinion. Connecting both of them this way creates a conflict in the viewer that goes beyond the binary world view of good and evil our culture wants us to believe in. The presentation of Doe’s character alone makes the movie a masterpiece to me, because it does not give us the easy answers we want. Seeing the murders makes it impossible not to think of him as evil but once you hear him talking, it’s significantly less easy. How can someone argue so well if he is supposedly crazy? Does the word “crazy” have any meaning anymore after seeing him?

Mills superficially is the hero, the fighter, the good man choosing to be transferred to a more dangerous precinct to find a challenge. In what is probably the central scene of the movie (which you will forget probably), he and Somerset have a conversation in a bar where he has some telling lines: “You want me to agree with you. You want me to say, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, you’re right. It’s all fucked up, it’s a fucking mess. We should all go living in a fucking log cabin.’ But I won’t. I won’t say that. I don’t agree with you. I do not. I can’t.” It’s hard not to admire his stance, but Mills’ problem is that he is both arrogant and ignorant. It is important to trying to fight and not give up, but that only works if you open your eyes and see what’s happening. Mills acts more on what he thinks he is supposed to do than on what he really thinks is right. That’s his downfall in the end, that he cannot read between the lines, that he cannot deal with moral ambiguities (in a world where morals are inherently ambiguous), that he only accepts easy answers.

That leaves us with Somerset. He always complains about people’s apathy and the terrors of his world, claiming that apathy seems to be the only way out. He has become deeply bitter and cynical through his job and the horrors he had to see in it, but also by the tragedies of his life, the decisions he regrets but can’t change, the loneliness that he claims is by choice, but that obviously pains him. You could ask if he makes any development throughout the movie. Tracy seems to have a big impact on him. There is of course the final line of the movie, the Hemingway quote about the world not being fine, but worth fighting for. You could argue that this is not the original ending, etc etc, but it is what we have and it sums up perfectly the conflicts of the movie. It combines Somerset’s ideas with Mills’ by looking at the world (this culture) the way it is (not fine), but insisting that you still shouldn’t give up. Try fighting (speak up, if you will) but be also aware what you’re dealing with. That thought is a nice beacon of light in this messed up culture.

Finally, the movie also makes some interesting comments about manhood, further distancing itself from the supposed misogyny of Tracy’s fate. Basically, any attempt of acting manly fails and the men who appear to be in charge all are kind of impotent. John Doe acts as if he knows exactly how the world works, but is detached from his bodily desires and throws up at the thought of sex. Mills always acts aggressively, territorial and with a lust for power. But throughout the movie he is put in situations where he is helpless and a victim to his instincts. There is a scene that embodies all of this as the SWAT team storms Victor’s apartment, following relatively traditional action shots of police cars driving and people running up stairs in their gear. When they break through the door by force, Somerset dryly comments: “They love this.” But what power does all their phallic battering rams and rifles give them? All they find is a victim that has been robbed of any possible defense. Their testosterone vaporizes in the most unmanly smell of air freshener trees. Fincher clearly deconstructs the idea of male heroes and among all the other amazing things Se7en achieves (and there is more I could talk about), this is just one more brilliant bit of filmmaking in a movie that is full of them.